The film 50 First Dates, set in Hawaii, revolves around Lucy Whitmore, an art teacher afflicted by anterograde amnesia, and Henry Roth, a marine biologist besotted by her uniqueness. A tragic car accident on her father’s birthday leaves Lucy unable to form new memories; each day is erased when she falls asleep, rendering her existence an unending cycle of the same day. Each morning, she awakens with no recollection of recent events, convinced it’s still the day prior to her accident. Her father, brother Doug, and friends carefully uphold the continuity of her world, from printing a duplicate newspaper to recreating her routine down to laundering her pink shirt daily. When Henry, previously known for avoiding commitment, encounters Lucy, he is captivated and determined to win her affection each day. His inventive approaches and eventual creation of a video diary enable Lucy to re-experience their shared moments, suggesting that love and patience can forge connections beyond conscious memory. The film interweaves humor and romance, offering a nuanced exploration of the profound challenges—and unique possibilities—of building a relationship with someone whose memories vanish each night.

Anterograde amnesia, a rare neurological disorder, impedes individuals from storing new memories, frequently leading to transient impairment; severe cases permanently obstruct the retention of new information. Unlike retrograde amnesia, which erases past events, anterograde amnesia preserves pre-existing memories while impeding new ones from transferring to long-term storage (“Anterograde Amnesia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment”). In 50 First Dates, Lucy exemplifies this condition as she reawakens each day, oblivious to anything beyond the accident day. The film’s portrayal aligns with medical knowledge that such amnesia commonly arises from traumatic brain injury, particularly in areas like the hippocampus. As Lucy’s condition stems from a severe car accident, she lives in a constant loop, unconscious to the time elapsed.

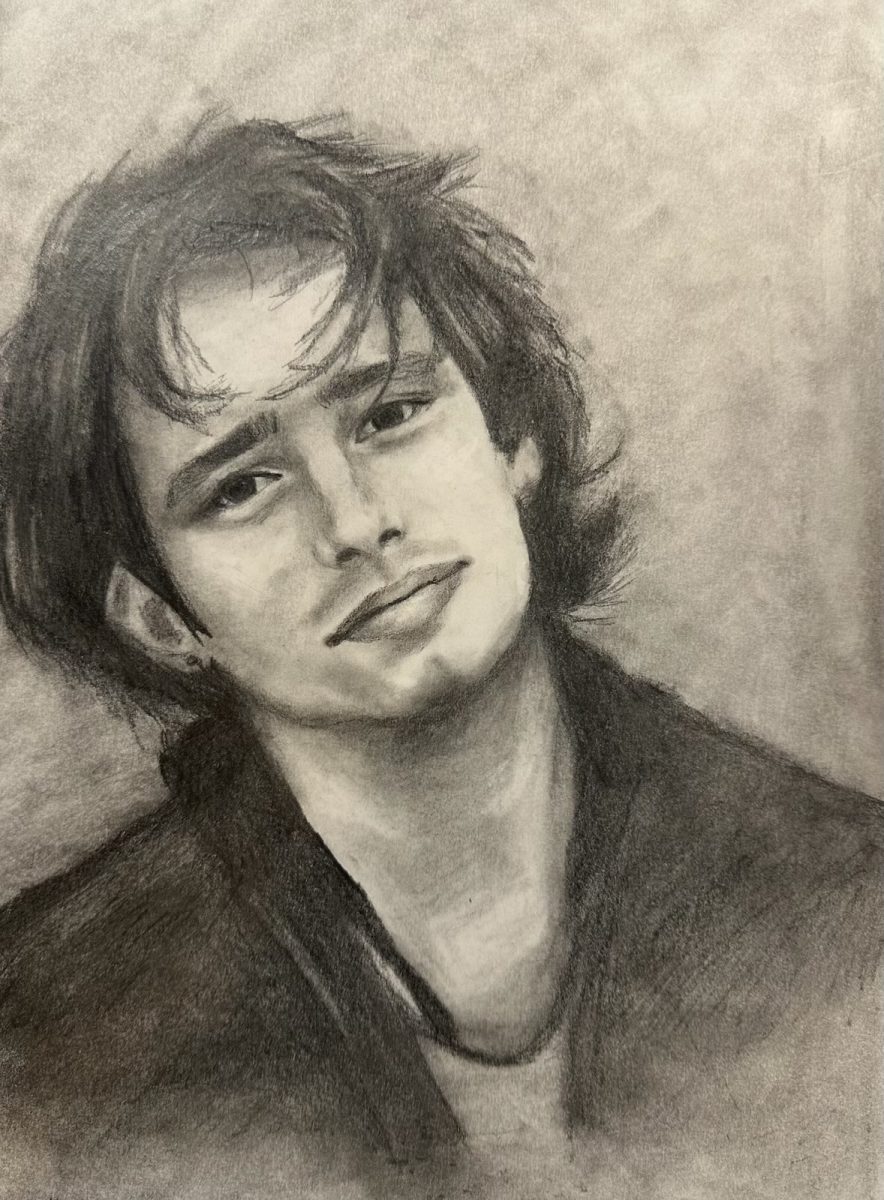

Toward the film’s conclusion, the depth of Lucy’s condition is poignantly revealed when Henry visits her at her job. Upon laying eyes on him, she instinctively leads him to view a collection of paintings at her studio—countless portraits she has created of him, despite lacking any conscious memory of their connection. This powerful scene underscores the complex nature of anterograde amnesia: while Lucy cannot explicitly recall Henry, she retains a profound emotional imprint of him that her mind translates into art. This reflects how, in anterograde amnesia, fragments of new memories can sometimes be encoded without conscious access (Brown), allowing Lucy to grasp a sense of familiarity and attachment even if she can’t recall the specific memories. The film captures both the limitations and nuances of living without long-term memory formation, illustrating how love and connection can leave traces beyond the barriers of conscious recall.

Real-world cases of anterograde amnesia reveal symptoms such as confusion, repetitive questioning, and a disoriented demeanor. Often occurring alongside retrograde amnesia or other cognitive impairments, the condition can stem from diverse causes, including brain trauma, degenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, or oxygen deprivation incidents such as strokes (“Anterograde Amnesia: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment”). Cases like that of H.M., an iconic example of anterograde amnesia, showcase the condition’s challenges—patients often retain procedural memory, such as motor skills, but lose explicit recall of recent events (Ogden). These distinctions emphasize the complexity of memory systems, underscoring the need for comprehensive support strategies for affected individuals. Family members of those with anterograde amnesia bear a unique burden. Daily interactions, punctuated by reminders and repetitive information, often lead to emotional exhaustion, frustration, and a deep-seated sense of loss. This is poignantly illustrated in 50 First Dates, as Lucy’s family constructs a stable reality for her. In reality, families of patients must balance compassionate care with their personal lives, frequently using journals or other memory aids to aid loved ones, though such methods only partially alleviate the heavy toll of an ever-evolving present. This dynamic between caregiver and patient, while romanticized in the film, underscores the essential role family support plays in helping individuals with anterograde amnesia navigate the complexities of daily life.

All things considered, 50 First Dates perfectly captures the stark reality of anterograde amnesia, offering a compassionate glimpse into the lives of those impacted by this condition. Through Lucy and Henry’s relationship, the film postulates that love has the power to transcend even the most arduous cognitive challenges. By highlighting the subtle and enduring impact of emotion on memory, 50 First Dates not only serves as an entertaining film but also raises awareness about the difficulties that are presented with anterograde amnesia and illustrates how, despite the constraints of memory loss, the human spirit and love can transcend even beyond the limits of remembrance.

Works Cited

“Anterograde Amnesia: What It Is, Symptoms & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23221-anterograde-amnesia. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Brown, Emily. “Anterograde Amnesia: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment.” Verywell Health, 31 March 2023, https://www.verywellhealth.com/anterograde-amnesia-7255000#toc-treatment. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Ogden, Jenni. “HM, the Man with No Memory.” Psychology Today, 16 January 2012, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/trouble-in-mind/201201/hm-the-man-no-memory. Accessed 1 November 2024.

50 First Dates. Directed by Peter Segal, performances by Adam Sandler and Drew Barrymore, Columbia Pictures, 2004.