Beauty, and the ritual of beauty: making the self beautiful, the routine of it, is a mechanism for simplification and control, as well as a form of socially rewarding self-abuse. I can reduce the emotional and intellectual complexity of my mind and my life by focusing on my exterior. Beauty is synonymous with goodness in most cultures. That feels like a safe place to be. I can switch everything off as I wash my face, shave the hair off my body, keep everything in line, and keep everything neat and clean. If I scrub away at my features, I can be blank. Then I can work from there, drawing who I’d like to be seen as on the medium of my body.

Women battling their appearances is not a recent epidemic, and it won’t end anytime soon either. Girls are thrust into positions of vanity early on in life, either being told that they should care about their looks or that they already care too much. This is not an isolated incident in their lives; they will be told this over and over again until age is the reason they are excluded from this equation.

After reading The Beauty Myth by Naomi Wolf, I figured it wasn’t too self-righteous to critique the world of wellness and beauty. It shouldn’t be taboo to critique the promotion of whatever reasonable to not-so-reasonable devices exist toward the beautification process. It seems pretentious to critique these matters because it is presented as shaming. It’s neither. As Charlie Squire puts it: “It is taboo to critique the concepts of makeup, cosmetic surgery, anti-aging, because it is received as “shaming” others’ “choices.” Why does there have to be shame? Critiques of these systems are not shaming others’ choices at all—they’re questioning the very idea of choice and of desire itself. An ad for an anti-aging product featuring a girl that looks no older than 16 advertises itself as the feminist alternative to botox because it is “non-invasive.” We see through our aesthetic Overton window, and this is the exact language and rhetoric that draws the curtains further and further closed. When the idea of aging naturally is fully removed from the conversation, it becomes self-care to prevent wrinkles, so long as you do it with these products marked with the correct trademarks. Contemporary marketing operates by transforming fear into desire. The fear of lacking control, the fear of being unwanted, the fear of aging, the fear of being oppressed are all repacked as the need for growth.” (There Is No “Choice” In Wellness Culture).

If the people who make these decisions themselves cannot offer solid reasoning or justification for the promotion of beautification, then are they even valid? Is there a reason others should do it? A common justification for promoting these ideas, be it makeup, surgery, or other gadgets, is always, “Why do you care what a woman does with her body? Why are you shaming her choices?” But again, the purpose of critiquing is not to shame but to find reason. I don’t question her perceived beauty, nor do I question her autonomy to make these decisions; I just would like to question what prompted these decisions, whether they involve me or not. I don’t condemn the use of makeup or cosmetic surgeries, and I don’t look down upon anyone who utilizes them (I’d be a hypocrite to critique the use of makeup or dieting entirely), but when we examine this issue at its roots, we can’t not question the effects. These cosmetic surgical complications are more common than the advertisements will let you know. According to the National Library of Medicine’s 2015 research report, 42.72% of people who undergo cosmetic surgeries experience complications that later affect the outcome of their appearance. So, in order to hide these complications, they get more surgeries—thus continuing the cycle. The most insidious aspect of the beauty myth and its cycle, according to Wolf, is its ever-shifting and unattainable nature. The ideal body size, skin tone, and hair texture are constantly redefined, ensuring that women are perpetually chasing the “ideal” characteristics and not themselves. This constant pursuit fuels a massive industry of cosmetics, diet products, and plastic surgery, all profiting from women’s anxieties about their appearance.

There is a disparity between men and women in this situation: women are typically expected to put more effort into “looking better,” and oftentimes, the standards may only be achieved by risky means. I am in no way saying that men aren’t affected by unrealistic standards and the low self-esteem that comes with it. I believe there should be more awareness raised surrounding men’s standards, but historically, women have faced much harsher criticism and scrutiny for not appealing to these standards. I don’t believe it’s fair for me to speak on behalf of men’s issues anyway. This disparity of the sexes is pointed out by Naomi Wolf, as she states: “Women tend to worry about physical perfection in a way that men seldom do because Genesis says that all men are created perfect, whereas Woman began as an inanimate piece of meat; malleable, unsculpted, unauthorized, raw – imperfect.” (The Beauty Myth, Naomi Wolf). Sociologically, we’ve traditionally seen women as extensions of men. They are smaller, weaker, and nugatory to men unless they are providing a service for their male counterpart; and if they don’t have a male counterpart, they need a reason why and must make up for it in some way.

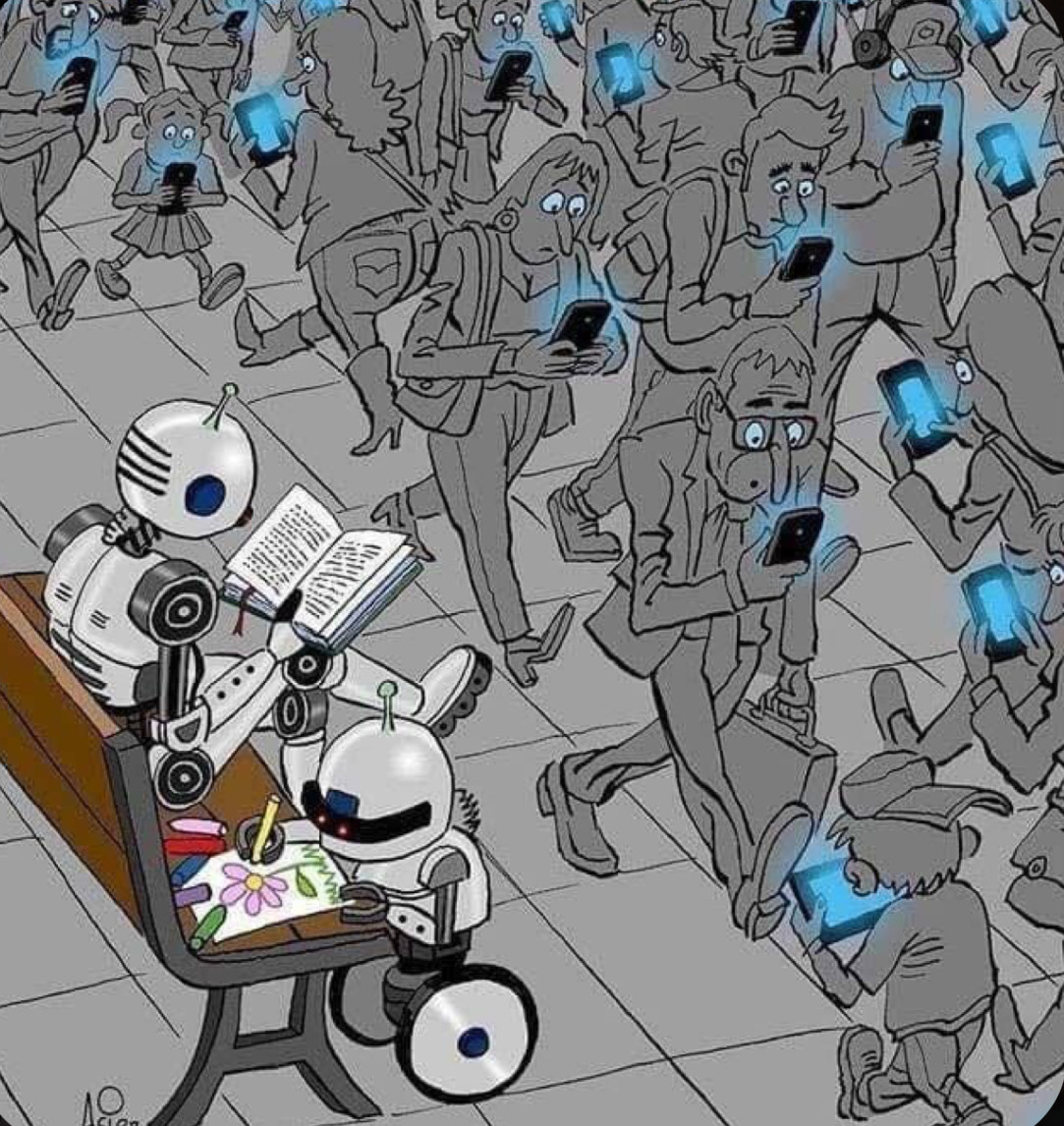

In the past two years, it’s been a joke on the internet that young girls, ages varying from five to fourteen, have been flocking to Sephora to get their hands on products far too mature for their young skin. This only validates my suspicion that for no girl is it ever too early to begin worrying about the ugliness of senescence. The lathering of retinoids and acids on baby skin serves no benefit to the girl but only to those profiting from telling her she needed it in the first place. Naomi Wolf’s points remain relevant in situations like these. Wolf argues that “the beauty myth” is not about physical attractiveness but rather the economic and sociological forces designed to control women by keeping them preoccupied with their appearances. And as the world becomes more and more politicized, the age of insecurities begins to drop. The desire to conjoin the self with a presentation of politics and collectivization becomes stronger because the need to be perceived in a particular way comes from the uncertainty of how we are already viewed. This examination of our outside slowly dissolves our insides– the less compassion we have for ourselves, the less we have for others. This is how women become perpetrators of the beauty myth and pass it down to the impressionable girls in their lives.

I don’t believe in natural beauty; I believe in making a convincing facade of it. I think some people are more blessed than others, but we all have to fight tooth and nail to achieve it. To pretend it’s easy is all part of the illusion.

Sources:

- “The Beauty Myth,” by Naomi Wolf

https://archive.org/details/beautymythhowima00wolf_1

- “Complications in Cosmetic Surgery: A Time to Reflect and Review and not Sweep Them Under the Carpet,” National Library of Medicine, Niti Khunger

- “There Is No “Choice” In Wellness Culture,” Substack, Charlie Squire